The ideal fusion fuel target doesn’t exist – yet. Researchers at SLAC are trying to change that.

To achieve peak energy output, inertial fusion energy targets must be perfectly symmetrical and perform under extreme temperatures and pressures. Researchers at SLAC are developing experimental techniques to evaluate new target candidates.

Key takeaways:

- Researchers are trying to design fuel targets that perform under the extreme conditions of a fusion reaction chamber, where temperatures exceed those of our Sun and pressures rival Jupiter's core.

- In four recent studies, researchers used SLAC's advanced X-ray imaging techniques to test potential target materials and validate computer simulations.

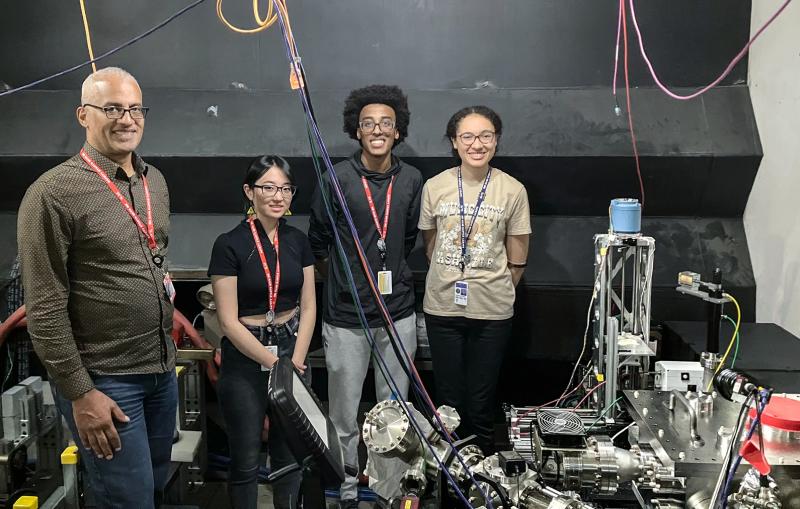

- Early career scientists led these first-of-a-kind experiments, shaping the next generation of fusion energy technologies.

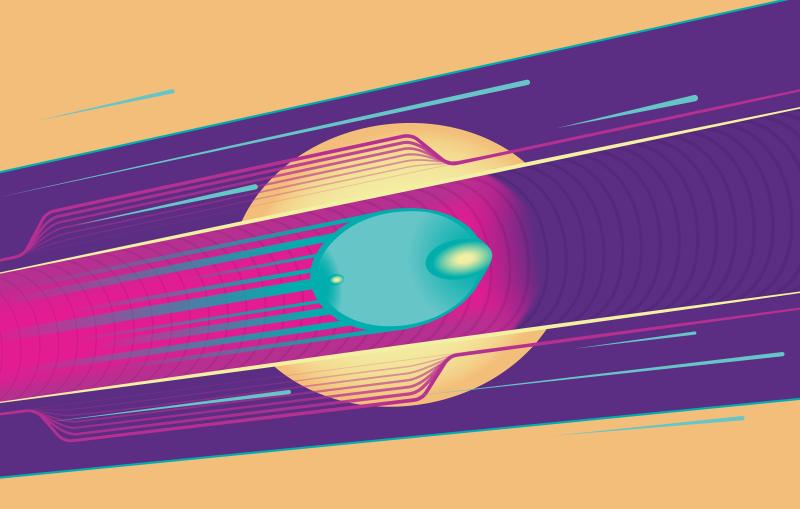

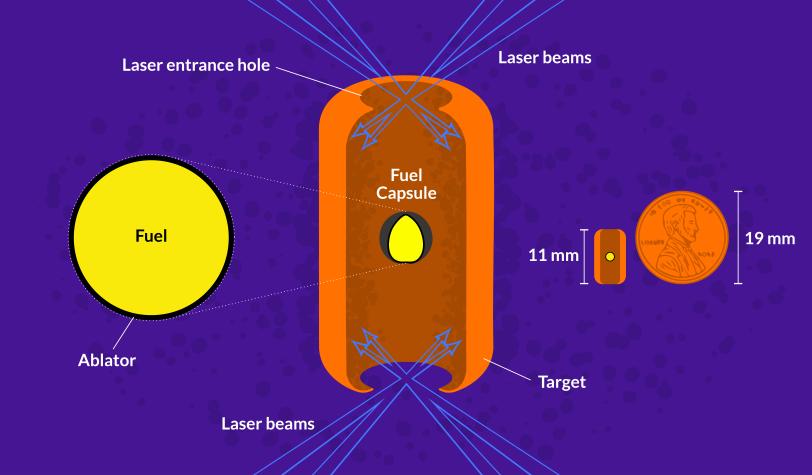

In an inertial fusion energy (IFE) reaction, a single fuel capsule, no bigger than a pea, carries fusion fuel into the heart of the reaction chamber. There, powerful lasers converge on the capsule, driving an implosion that fuses the fuel atoms and unleashes a surge of energy to rival the stars.

Before IFE is ready for the United States power grid, several technical advances need to be achieved. One key challenge is the successful design of fusion fuel targets: complex cylinders housing multiple components needed to enable a reaction, including tiny, precisely engineered capsules that hold the deuterium and tritium fuel.

What is inertial fusion energy?

SLAC experts explain the science behind IFE, an approach to generating energy using fusion fuel and lasers.

The Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is conducting experiments to improve the design of fusion fuel targets. The work is part of the DOE Inertial Fusion Energy Science & Technology Accelerator Research (IFE-STAR) program’s RISE Hub.

Designing effective targets is a tall order. Researchers must understand how potential materials respond to the intense heat (hotter than the Sun) and pressure (greater than a planet's interior) imparted by the high-power lasers. To maximize energy output, each fuel capsule must compress symmetrically, without defects, voids or impurities. And, because future fusion power plants will use an estimated 10 capsules every second, they must be easy to mass produce.

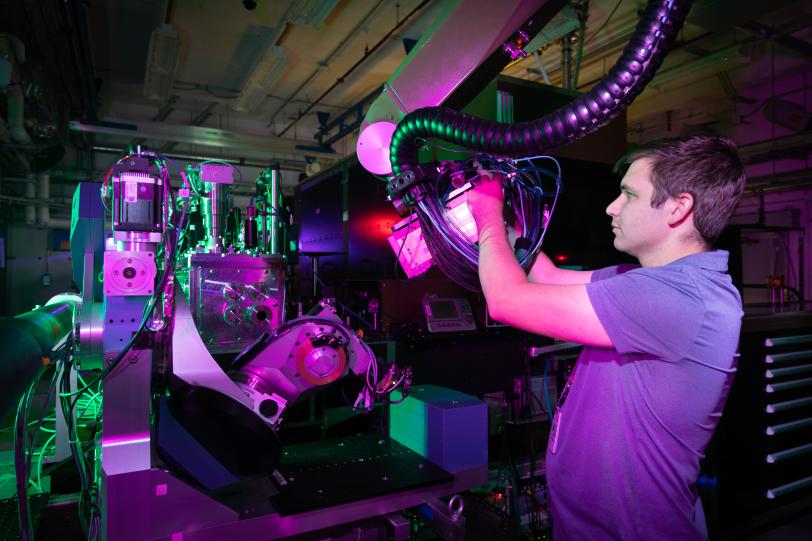

Four recent studies performed at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) and published in Physics of Plasmas provide new insight into how a promising class of fuel capsules – 3D-printed foams – perform under extreme conditions.

“At SLAC, we’re inventing new ways to study these fusion fuel targets and their potential behavior under the extreme conditions of a fusion power plant,” said Arianna Gleason, SLAC staff scientist and deputy director of SLAC's High Energy Density Science (HEDS) division. “These four studies, each led by early career researchers, not only tell us about specific targets – they outline experimental frameworks for future temperature, pressure, density and imaging studies.”

Taking the temperature

One study focused on the problem of temperature. Researchers want to understand how various target candidate materials will react to the intense heat in the earliest stages of the laser interaction – when will the material transition from a solid to a plasma? How much of the energy goes toward heating versus compressing the target material? These questions have big implications for a target’s ability to survive and perform in a fusion power plant, but the nature of high energy density plasma makes such measurements incredibly difficult.

At LCLS’s Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument, a research team laser-heated carbon samples – a standard material used in fusion targets – then probed the samples with ultrashort bursts of X-ray light. Using a unique combination of spectroscopy and scattering techniques, the researchers were able to capture time-stamped temperature measurements, revealing how the samples evolved over time.

“By bringing together two X-ray diagnostic techniques – Thomson scattering and fluorescence spectroscopy – we were able to cross reference our temperature measurements and build up confidence in our results,” said Willow Martin, lead author on the study, PhD candidate at Stanford University and member of SLAC’s HEDS Division. This novel technique paves the way for more accurate temperature measurements of target candidates.

Making shockwaves

Another study explored how shockwaves move through different target materials. Using the MEC instrument, the team imaged a new fuel capsule candidate – 3D-printed TPP (two-photon polymerization) foams – as shockwaves comparable to those created during inertial fusion reactions traveled through the material. They tested various densities of TPP foams alongside conventional aerogel foams, capturing high-resolution images with ultrashort X-ray pulses to compare how each material responded to the shock compression.

“As physicists, we want to work with idealized geometries – targets with perfect symmetry and zero imperfections – but reality gets in the way. These real-world results will help us validate simulation models, which help us predict how different targets will perform,” said Claudia Parisuaña Barranca, lead author of the study, a graduate student at Stanford University and member of SLAC’s HEDS Division.

Building 3D reconstructions

Defects – even at the scale of microns – can make or break a fusion fuel capsule. One study sought to image TPP foams with minute precision for the first time. At LCLS’s X-ray Pump Probe (XPP) instrument, a team imaged a single pillar of a TTP foam, just 10 microns wide. Using a technique called ptycho-tomography, they captured X-ray diffraction patterns and built detailed 2D and 3D images.

“When you’re working with low density materials that don’t diffract many X-rays, it’s a real challenge to extract meaningful data from the experiment,” said Levi Hancock, lead author on the paper, undergraduate student at Brigham Young University (BYU) and former Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internships student with SLAC’s HEDS Division. “Given the low scattering, getting any 2D reconstructions at all felt like a miracle. Despite those challenges, the 2D images still helped us create a really well-defined 3D reconstruction.”

This data, too, will help researchers improve fusion simulations and design better target materials.

Imaging the void

Tiny imperfections, or “voids,” in a fuel capsule’s outer shell can also sap energy from fusion reactions. Simulations try to account for this impact, but scientists have had little real-world data to validate their models.

“If we can fully understand the physics of void collapse in ablator materials by performing real experiments and comparing those results with simulations, then we can learn how to better design the targets, minimize the impact of those imperfections and improve simulation models,” said Daniel Hodge, lead author on the study and graduate student at BYU.

At the MEC instrument, a research team deliberately created voids in capsule samples, then blasted them with laser-driven shockwaves. They tracked how the voids influenced the way materials compressed under extreme pressure.

Using multiple imaging techniques, researchers reconstructed the structure and density of a single sample subjected to laser shock compression; this data will help researchers see where computer simulations succeed – and where they fall short.

A fusion-fueled future

"These studies set the stage for the next phase of IFE target research, and they are being led by the next generation of fusion scientists," said Gleason.

The lead authors on these papers – all early in their careers as researchers – each point to a passion for this field that drives them forward.

Fusion energy

Dive deeper into fusion energy research at SLAC

“It’s a grand scientific challenge, to make fusion energy a real, sustainable power source,” Martin said. “Contributing to a technology that could be so revolutionary for human society is a strong motivator that keeps me plugging away, even when data is noisy, or experiments don't go as planned.”

“I had just started undergraduate research in 2023 when the NIF [National Ignition Facility] announced that it had achieved ignition. That's when I decided I wanted to do fusion research,” said Hancock. “SLAC has helped me connect to the broader IFE research effort, while also letting me take charge of my own project. For an undergrad, that’s a pretty unique experience, and one that really sets me up for my future.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research is supported in part by the DOE Inertial Fusion Energy Science & Technology Accelerator Research (IFE-STAR) program’s RISE hub, led by Colorado State University.

Citations:

W.M. Martin et al., Physics of Plasmas, 01 July 2025 (10.1063/5.0267033)

D.S. Hodge et al., Physics of Plasmas, 22 August 2025 (10.1063/5.0272820)

C. Parisuaña et al., Physics of Plasmas, 27 August 2025 (10.1063/5.0273572)

L. Hancock et al., Physics of Plasmas, 10 October 2025 (10.1063/5.0272192)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.